Vulnerability and Response‑Ability in the Pandemic Marketplace: Developing an Ethic of Care for Provisioning in Crisis

Susi Geiger · Ilaria Galasso · Nora Hangel · Federica Lucivero · Gemma Watts (2023)

The Covid-19 pandemic turned the mundane act of shopping into a situation layered with practical and epistemic uncertainties. The concentrated physical space of the supermarket became a microcosm for relational ethical reasoning in moments of crisis.

Against this scenario, we explore questions such as: What does it mean ‘to care’ and to be ‘ethical’ in the context of a crisis? What happens in times of crisis when emotions such as fear and insecurity intrude into and disrupt shopping practices? What changes are brought about when people shop not only as a way to care for themselves and their close ones, but also to exert responsibility toward others or society at large in a situation of crisis? How are shopping practices shaped when they are carried out in a physical space that lays open people’s vulnerabilities?

This paper draws on the ethics of care to investigate how citizens grappled with ethical tensions in the mundane practice of grocery shopping at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic. Drawing on Fisher and Tronto (1990, p. 40), we define care as “everything that we do to maintain, continue and repair our world so that we can live in it as well as possible”. We use this case to address the broader question of what it means ‘to care’ in the context of a crisis. Based on the SolPan qualitative longitudinal cross-country interview study, we find that the pandemic transformed ordinary shopping spaces into places fraught with a sense of fear and vulnerability. Our participants responded to these multiple demands by adopting different degrees of “response-ability”—which we define, leaning on Haraway (2012), as the capacity of people to respond to ethical demands through situated ethical reasoning. Utilizing the ethics of care and particularly Joan Tronto’s (2013) notion of ‘caring with’, we capture how a sense of embodied vulnerability, political responsibilization, and people’s own situated capacities to respond all play together to form a particular ethos of care in periods of crisis.

Through close analysis of a large set of in-depth interview data collected in four countries (Germany, Ireland, Italy, and the UK) at two intervals during the pandemic (spring and autumn 2020), our study highlights care as a practical ethos in practices of provisioning. The striking similarities in participants’ ethical reasonings that we identified across the four countries give us a deep understanding of people’s ethical reasonings in the context of shopping in crisis. Our findings support care ethics scholars’ calls to replace an abstract and prescriptive morality with a situated, relational ethics of care (Ryan et al., 2023). Shopping during Covid-19 became a key moment where usually difficult to elicit and/or habitual behaviors and thoughts were disrupted and thus opened up to reflection.

We propose that shopping is not just a lens to understand the fabric of relationships with proximate and more distant others, but also an entry point to understand the personal and social tensions that an awareness of fundamental interdependency creates. We argue that how people coped with a crisis context can hold valuable lessons for consumption ethics beyond the current ‘pandemic moment’, lessons that may be extended to broader ways of interdependent ‘ethical living’ (Ariztia et al., 2018) in our current era of poly-crisis: while queuing in front of shops is history, at least for now, what may stay with many of us is an awareness that going about one’s daily errands could extend to a more response-able way of interacting with fellow shoppers and marketplace employees.

This study is published in a scientific journal:

Geiger, S., Galasso, I., Hangel, N. et al. Vulnerability and Response-Ability in the Pandemic Marketplace: Developing an Ethic of Care for Provisioning in Crisis. J Bus Ethics (2023). doi.org/10.1007/s10551-023-05541-7

Breaching, bridging and bonding: How radical and moderate work intertwines for patient-centric innovation

Journal of Management Studies – Blog

Geiger, Susi and Emma Stendahl (2023)

For social movements, is an institutionally accommodating approach more or less likely to affect societal change than more disruptive activities? And if both approaches serve different purposes toward a common goal, how can they most fruitfully be combined? We tackle these vital questions in a context where a small patient movement advocating for patient-centric technology innovation has tackled highly entrenched institutions. We trace how this movement succeeded in affecting change through three different pathways – breaching, bridging and bonding – by distributing and intertwining relational, material and discursive social-symbolic work over time.

Pushing for patient-centric innovation

Our recent paper published in the Journal of Management Studies uncovers how heterogeneous and distributed forms of social-symbolic work combine over time to yield synergistic relationships that precipitate institutional change. We studied a group of patients and parents of children with Type 1 diabetes (T1D) who started to challenge the technological and regulatory standards of T1D healthcare. Under the hashtag #WeAreNotWaiting, the community set out to foster interoperability in T1D technology, to ‘close the loop’ between separate medical devices, and more broadly to show industry and regulators that they had to innovate alongside patients.

Radical Flank effects and Social-Symbolic work

In the social movement literature, one long-standing conundrum has been to establish whether and in what contexts radical and moderate collective action can combine to change a societal status quo. On the one hand, change needs to be acceptable to institutional incumbents or it may be quashed, so too much disruption might be counterproductive. On the other hand, if the disruption can easily be absorbed or ignored by institutional incumbents, real change may never happen. In some cases, the use of radical approaches by challengers may help the overall cause by making the moderate voices more palatable to incumbents; a phenomenon that social movement theory has termed the ‘radical flank effect’. However, research in this area has had less to say about how more or less radical practices might intertwine over time in realizing these positive effects. For this reason, we combine insights from the radical flank theory with literature on social-symbolic work to shed light on the interweaving repertoires of action that different movement actors pursue in institutional change projects over time.

Interweaving pathways of change

Our longitudinal analysis of Twitter data, interviews and observations reveals three broad social-symbolic work ‘pathways’, which proved highly complementary over time and which contributed to technological and regulatory change in T1D healthcare. The ‘breaching’ pathway included activities that disrupted industry incumbents and regulators and created pressure on them through material breach work and discursive breach work– in our case, ‘hacking’ commercial T1D technology, risking legal persecution and challenging existing regulations through broadcasting and explaining the motives behind this material work. Those who engaged in the ‘bridging’ pathway seized on this institutional breach but pursued a more moderate pathway to change; this pathway saw members collaborating with industry incumbents and regulators to co-develop T1D technology through material and relational bridge work. Situated between these two pathways and keeping them aligned around shared goals, the ‘bonding’ pathway included values work and amplification work, which corralled the community and helped sustain the collective effort.

Maintaining the pressure and accommodating incumbents

With our processual framework, we propose that this success in paving the way for patient-centric technology innovation in T1D care is because of how more radical and more moderate work types were sequenced, aligned, and integrated across the breaching, bridging and bonding pathways. In our case, this led to a change that was revolutionary in pace but developmental in scope – Micelotta et al. (2017) have termed this type of change ‘institutional accommodation’. We found that where the radical ‘breaching’ work provides impetus for change and maintains the pace and pressure for change to happen, work in the moderate ‘bridging’ pathway continually reinserts this change into institutional givens, preventing it from becoming too institutionally disruptive. We highlight the importance of the ‘bonding’ pathway as an important social glue that prevents these pathways from drifting apart over time. Overall, we draw attention to the fact that institutional change projects require multifaceted collective material, discursive, and relational work, which may often emerge organically, but which needs to be carefully aligned to affect change. Studying change in the area of patient-driven technology innovation, our case lends itself particularly well to moving beyond an emphasis on discursive change strategies by emphasizing the importance of material breach work to trigger institutional change. We define material breach work as the illicit altering of material artifacts that are central to an institution’s or organization’s practices. At the same time, we highlight how this work needs to be framed by other types of work to achieve its intended effects.

Small movements can achieve change

Our study contributes fine-grained processual insights into the radical flank and social-symbolic work literatures. But we also offer contributions beyond the academic setting by demonstrating how relatively small and resource-poor movements can impact societal challenges. We recommend that social movement actors carefully reflect on how they might distribute and sequence different types of social-symbolic work, particularly in traditionally change-resistant contexts such as healthcare. This might mean focusing on more radical breaching work first, to gain momentum, and then activating a bifurcated approach, where radical and moderate work proceeds in parallel but is tightly aligned. Bonding work is vital throughout to remind all actors of the social movement’s core values. Overall, we argue that it matters less who does what type of work (that is, whether in one social movement one is in the ‘radical’ or in the ‘moderate’ camp); what matters is that all types of work – breaching, bridging, and bonding – are pursued for change to take place.

Covid-19 vaccine: to whom and why?

An overview of the Irish data

Drawn upon data collected in the context of the multinational study

“Solidarity in times of a pandemic“

By Dr Emma Stendahl, Dr Ilaria Galasso and PhD candidate Ongolly Fernandos – February 2021

If it’s free, you are the product – The perils of assetizing consumers’ genetic profiles

Geiger, Susi & Gross, Nicole (2021)

There’s an old adage that encapsulates our relationship to many of the digital products we consume, from social media to apps to email programs: “If it’s free, you’re not the customer, you’re the product”. But what happens in an industry where this ‘you’ really means – well, you? Your genetic profile and other health information about you? Information that you may never thought you’d share?

Our paper ‘A Tidal Wave’ explores the business models of consumer genomics companies, such as 23andMe or Ancestry, to find out how the consumer becomes the product in this industry, or as we phrase it, how these companies ‘assetize’ their genomic databases.

There’s a lot of talk about data privacy in healthcare, which is great; after all, information about our health really is the most sensitive of all data. However, we think that one can only really understand how privacy can be safeguarded when we understand how companies profit from this data.

Solidarity in Times of a Pandemic – Irish Overview (from 1st round of interviews)

by Dr Ilaria Galasso – November 2020

Why We Need To Talk About

Access Now!

By Prof Susi Geiger – October 2020

We are at a critical juncture both in Ireland and in Europe with access to medicines. We’re in the middle of a pandemic (no news there!); we’re also embarking on a new round of negotiations between the pharmaceutical industry in Ireland and the government for a framework agreement for the supply of medicines, and the EU are currently planning their future Pharmaceutical Strategy.

I think it’s clear to many in the sector that the ‘old’ system of health technology assessment using measures such as Quality Adjusted Life Years (or QALYs), supplemented by case by case medicine reimbursement decisions, doesn’t reflect the reality of a highly technologized and personalized biomedical industry anymore. From now on, pretty much every (branded) medicine that will reach the market will be priced further out of reach of even the richest healthcare system. The inadequacy of just doing more of what we’ve been doing so far is exacerbated by the demographic timebomb we’re facing with an ageing population, by a highly complex and fragmented decision making system, and now of course also by a pandemic that has shone a bright light on every health system’s weaknesses.

So rather than tinkering around the edges with another round of price negotiations between the pharma industry and government, we need a strategic and high-level rethink of the drugs access system here in Ireland and beyond. We need more coordination between all the different bodies that are involved, which has to include civil society and patient perspectives, we need to consider the full lifecycle of medicines, from patenting to early horizon scanning to making sure that patients on the ground can actually access them in their local area; we need to think about supply chains and potential manufacturing shortages, and we need to look at budgetary responsibilities. While it is often tempting to speak of the high-cost new medicines, we cannot forget that a lot of lower cost medicines are also sometimes unavailable or cost more than they should, simply because there isn’t enough competition in the market (don’t get me started on the IP system that causes this lack of competition). And we have to take account of socio-economic and regional disparities of access as well. To think about these issues it is helpful to break this birds-eye view down in terms of the three components that the WHO talks about: access, availability and affordability (plus, of course, quality!). And to realize that all components go hand in hand.

Expanding this thinking to the European plane, the pandemic has left no-one in doubt that health issues know no border and that if Europe wants to be a greater whole for its citizens then we have to think about healthcare access beyond the Irish borders too. At the very least we have to ensure that what we do in this country is aligned with developments elsewhere. I would argue that this ‘elsewhere’ should include the globe, but let’s be a little more modest and focus on Europe for now.

And in fact the past couple of years have seen the issue of medicines pricing and access to medicines in the spotlight like rarely before– and that’s even before Covid-19 happened. Just to retrace a few of these developments:

- There was the transparency resolution that was raised by Italy in May 2019 at the World Health Assembly and adopted (against pressure from some countries), which compels pharmaceutical firms and governments to “Take appropriate measures to publicly share information on the net prices of health products”. In fact, Italy has just passed a decree to implement this directive, as the first country world-wide.

- Around the same time, the Dutch minister for health Bruins put together a proposal to reduce the patent period for European pharmaceutical patents from 10 to 5 years. This was in parallel with a public consultation by the European Commission that scrutinized patent incentive tools such as supplementary protection certificates, market exclusivities for orphan designations, data protection and market protection. The report found that not only did a lot of companies use many of these tools in parallel, but that they also had a very strategic approach to choosing when and in which European countries they would make their products available. Not all new products are made available in all European countries at the same time, and often they were introduced such that if there was reference pricing within Europe the points of comparison were the higher-priced countries.

- Then, also in 2019, there was of course the high-profile case of Vertex’ prolonged fight with the UK government over the pricing of Orkambi, which was only resolved when the UK government threatened the use of a compulsory license for Orkambi.

- The possibility of using both compulsory and voluntary licensing agreements came back into the spotlight in the past few months, with Costa Rica proposing the use of a voluntary licensing pool for Covid19 medications (the so-called C-TAP), with some countries also calling for a higher willingness of the use of compulsory licensing in public health emergencies.

Let’s not forget the current EU consultation over its future Pharmaceutical Strategy. Interestingly, while emphasizing the innovation principle and the functioning of the internal markets, this strategy puts a clear focus on fiscal sustainability and patient access. Specifically, the Context paper identifies, in its own terminology, the following ‘market failures’:

- The EU’s exposure to current and future health crises and the possibility of a coordinated response, given distributed competencies between the Commission and the individual states (we saw in the current pandemic that individual national approaches often don’t make a lot of sense).

- Unequal access to medicines that are not always affordable for patients and for national health systems across the EU, particularly in the areas of focal pharmaceutical innovation (typically highly lucrative medical markets).

- Innovation efforts that do not correspond to urgent public health needs, with firms navigating toward the higher-value R&D and issues such as antimicrobial resistance being inadequately served;

- Financing for smaller European pharmaceutical and biotech firms that doesn’t depend on venture finance or targeting being acquired by Big Pharma.

- Missing regulatory frameworks for novel scientific advances such as AI and digital health, where current pharmaceutical regulation is often just completely inadequate.

It is fair to say that an awful lot has been happening at EU level in the past two years, and I think it is equally fair to say that the awareness among policy makers and governors that the medicines market is absolutely ripe for a fundamental rethink has been spreading quickly.

We need clear quantifiable indicators for the socio-economic benefits of medications. The industry often voice their unhappiness with the current Health Technology Assessment processes, but the so-called ‘value based’ system of referencing pharmaceutical prices against savings compared to the status quo like we see it in the US for instance will invariably lead to price inflation, as the ‘value’ of doing nothing a lot of the time is incalculable.

A fair price for medicines is one that covers the cost made by the seller (including R&D, manufacturing and distribution, and fair profit) and assures affordability, value to the individual and the health system and security of supply to the buyers. Fair access to medicines is something that should not be decided on a case by case basis but on the basis of a universal health system and sound supply chains based within Europe, without a two- or three tier society either in this country or across Europe. We absolutely need a thriving pharmaceutical industry, and the current crisis has certainly demonstrated that again, but now is the time to think creatively about how we interact with this industry. We need governments to fund public innovation and R&D and to put conditionalities into these investments if this is done in conjunction with private industry, so that the public doesn’t have to pay twice for medications. In the longer term, we need to think about possibilities of decoupling the R&D process from the market aspects of the pharmaceutical lifecycle altogether. Most pressingly, we have every right to ask the industry for more transparency in pricing and R&D costs. This would give us all a much firmer basis for discussion and decision making, which at the end of the day needs to revolve around the fact that health is a human right and not a market object.

Crisis Ruminations

By Dr Simeon Vidolov – September 2020

It was back in November 1989, when for the first time in my life I witnessed a historical event that set my home country Bulgaria on a new path. The communist party leader and prime minister resigned after some 40 years of ruling. This event marked the beginning of the end of the Soviet-era in Bulgaria. The wind of change was blowing in Eastern Europe leading to the end of the Cold War; and the fall of the Berlin Wall symbolized a new beginning, and a future filled with hope and enthusiasm.

Even by the stretch of the imagination it would have been difficult to predict what was to follow in the upcoming years. After a sequence of financial, political and food supply crises, the initial hope and enthusiasm faded away and gave way to desperation and pessimism. I remember queueing for hours in front of the local grocery shop in the Summer of 1991 to receive the rationed food supply. Following the liberalization of prices, the rationing system was the only means to secure equal food distribution. The transition from a totalitarian regime and centrally planned economy, to a democracy and market economy, generated various crises that still conjure up vivid memories. Some of them were related to the financial crisis in 1996/97, when a hyperinflation of more than 1000 percent led to yet another collapse of the Bulgarian economy, with shelves bereft of staples and snaking queues in front of banks. This crisis was also a source of change, leading to the election of the first reformist government, that also coincided with my first year in the university and the end of its full term with my departure from Bulgaria, never to return permanently.

A recent article, related to the Covid-19 pandemic, claimed that the average European citizen goes through four major crises in a lifetime. In many ways the Covid-19 crisis has been reminiscent of the experiences I’ve had in the 90s. In particular, the long lines in front of shops and the pervasive sense of ‘crisis’ and insecurity were already viscerally familiar. Beyond the feeling of being a deviant case in such statistics, I’ve wondered about the appeal of using crisis as a measuring unit of human life. Clearly, one performative effect of such writings is the normalization of crisis rhetoric and positioning it as an indelible part of contemporary societal discourse. I don’t disagree with Giorgio Agamben, that the notion of crisis does more than just describing a particular state of affairs and has a performative role as an instrument of power in legitimizing certain political and economic decisions. Yet, I also think that it illuminates important aspects of our contemporary world and human condition, which can also open new possibilities for a common future. After ruminating on these ideas for some time, I’ve realized that crisis, both as a notion and experience, has been an indelible part of my life. Let me elaborate below.

My first more intellectual encounter with the notion of crisis was in UCD during my PhD studies. I was fortunate to be introduced early to the work of Anthony Giddens. Giddens, together with Ulrich Beck, whose famous work was the ‘Risk Society’, were two of the key theorists of the contemporary world and modern society. While they don’t explicitly discuss crisis, their writings sensitize us to the crisis-like aspects of social relationships and identities in the contemporary globalized world. The qualitatively different nature of risk and trust, and the anxiety and psychological insecurity that shape the contemporary way of living and working, are brought to light in their books. As a junior researcher following the critical tradition in organization and technology studies, these insights and ways of perceiving different social phenomena became formative of my research sensibilities. While I had a critical stance towards the dominant formal and normative approaches in organizations, I also came to realize that plans and methods were important as collective psychological defences cultivating a sense of predictability and security. Plans, rules and methods played a role in organizing, coordinating and managing collective activities, but they also often drifted and were enacted exhibiting subsidiary political and social implications. Around this time I also read Latour and Woolgar’s ‘Laboratory Life’, and came to appreciate the role of ethnographic studies in uncovering the actual messy reality that usually significantly departs from the normative methodological prescriptions and the sterile representation of the reality they convey. Through the writings of Weick and Sutcliffe, I also learnt that adhering to rules and plans was not an appropriate approach in dealing with incidents and crisis situations. In their book on High Reliability Organizations (HROs), Weick and Sutcliffe describe how nuclear power plants rarely rigidly adhere to pre-determined plans and rules, but let people on the ground improvise and rely on their expertise and situated assessment to respond to the unexpected and high risk situations. I had already learnt this lesson working for the Red Cross as a sea lifeguard for a couple of summers. It was a difficult lesson to learn, that in rescue operations it is best to be flexible and open, and to respond to whatever the particular situation might call for.

Such lessons don’t come along easily, but they are learnt and embodied through making mistakes and embracing uncertainty. This echoed the work of Martin Heidegger and of Hubert Dreyfus, who became profoundly formative of my understanding of how we act, solicit and navigate the social world. Bert Dreyfus offers valuable insights into how we become experts by abandoning the rules and dropping the tools, and foregrounding the importance of making mistakes and brooding over difficult and emotionally challenging choices. These are the ways through which we develop our gut feelings and expert judgements. Crises then, big or small, are important for developing our skills and expertise.

I was further exposed to the concept of crisis when I took a PhD module from the UCD School of Philosophy delivered by Dermott Moran. The course aimed to introduce the work of Edmund Husserl and particularly his series of lectures titled ‘Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology’. Husserl back in 1934 saw the crisis in the gap between scientific objectivity and rationality, on one hand, and their practical and ‘spiritual’ roots, on the other hand. He predicted that the separation between people and science, and ignoring the subjective and everyday origins of science, might lead to bleak consequences. A prediction that some argue materialized with the start of WW2 a few years later. Crisis in this sense is long-lasting and simmering, and can become taken for granted over time.

A few years later, when I started teaching in UCD, I often started my modules with reference to Husserl’s ideas on crisis. Crisis comes from the Greek krisis that implies pulling apart and separating. What Husserl cautioned us some 90 years ago still seems valid today for Management and especially Information Systems disciplines – this is, the natural science approach, focused on measurement, formalization, and calculation, translated in the separation between the technical and the social or rational and affective. The development and implementation of methodologies and technical artefacts often obliterate the actual human experiences in the management of organizations and technologies. Forgetting and ignoring the foundational role of everyday processes, of ‘sociologic’ rather than logic, reinforce the crisis. In many ways my research has been focused on dealing with this ‘krisis’ – identifying the cleavages or dualisms, and illuminating their negative implications for organizational and social practices.

Many of the avant-garde conceptual perspectives I was interested in, such as phenomenology, practice theory and ANT, have a more composite and hybrid approach, overcoming the ‘krisis’ and emphasising the ontological inseparability and performativity that encourages new ways of thinking, speaking and acting. In certain ways my research has been following the ‘critical’ tradition, not only in a sense of critical theory that is focused on the inner workings of politics and underlying power structures, but also as an adjective of ‘krisis’, or dealing with the atomistic and positivistic dualisms, bifurcating and in this way simplifying the world, and how we come to know and experience it.

When I moved to Barcelona to be a Marie Curie post-doctoral fellow, crisis became even more central to my research, but in a different, more empirical way. My position was on a project in the area of crisis management, and crisis in this context means a critical event or incident. In many ways this connotation departs from Husserl’s long-lasting and enduring state of crisis. Crisis here is related to an ancient medicine meaning of judgement, when the doctor noted at the decisive moment whether the sick person would survive or die. In line with this, decision-making and information management are central processes in responding to crisis and disaster situations. Such crises can be different types such as natural disasters or man-made like war conflicts. In either case they are extremely disruptive and harmful, and can be traumatizing and emotionally scarring.

Crises, however, also uncover and evoke important aspects of human nature including kindness, care and empathy. I was fascinated by the altruism and bravery of volunteers in times of crisis. I was surprised to find out that volunteerism was also taking place through digital media where the digital traces left by the affected population offer valuable information about the state of crisis and its impact. I became one of the digital volunteers, collecting and analysing social media data with a view to supporting people on the ground and facilitating the operations of the responding organizations. As a researcher I was interested to understand the transformations of the crisis information management practices and how these changes were transforming the whole humanitarian aid system.

During this period, I was also struck by a personal crisis that involved decisions of life and death. As a caregiver I had to navigate national healthcare systems and handle the administrative and emotional burden. It was then when I also realized that being a patient and a caregiver was also affected and undergoing a transformation afforded by digital technologies. One could seek support and information from other patients, organized in online communities, seeking to alleviate the uncertainties and anxieties of a disease. Currently as a member of the MISFIRES team, digital health and healthcare activism have become the focus of my research.

Going back to where I started my ruminations. The Covid-19 crisis has introduced various separations: between now and before, between families and co-workers. Physical separations probably never witnessed in the recent decades. It has also triggered a high degree of uncertainty and anxiety, and has further re-enforced the rhetoric of crisis. It has also uncovered new types of risks and vulnerabilities for which the humankind hasn’t been prepared. Coping with the challenges of this crisis, we have also learnt important lessons. For one thing, handling the Covid-19 pandemic has been anything but a simple and straightforward process of setting rules, using rigorous methodologies and objective data for managing and alleviating the crisis conditions. The reality has been much messier and ambiguous, the process has involved trial and error with multiple adjustments and experiments. We’ve been all pulled apart and separated, but we’ve also been in very similar circumstances, struggling with the same challenges. To put it differently, we’ve been separated together. And these inherent and often invisible links that have always already connected us all is probably what we shouldn’t allow ourselves to forget.

In a Heideggerian sense, this krisis is giving us an opportunity to stand back and see the world we are living in through a different lens; a lens that can help us uncover our role and our decisions in the incipient becoming of the world, and point to new possibilities and modes of relating, working and living. Let me mention a few of these below:

Family living – many of us having spent considerable time in our homes over the last few months have probably experienced difficulties in navigating and organizing family lives. This experience hopefully has given us a better understanding of each other’s needs and has taught us how to cultivate better relationships with our loved ones.

Social living – we have all at some point of time acknowledged how much we miss our extended families and friends. Many of us have probably come to realize that we are not simply individuals that can easily connect and disconnect, but are rather co-constituted by our social relationships; and in this way hopefully we’ve come to accept and appreciate our similarities, but also our differences.

Organizational living – underneath the neoliberal organizational machinery, our ‘humanness’ has transpired. Having shared the difficulties of working from home and physical isolation, the Covid-19 pandemic has uncovered our individual and collective vulnerabilities. These experiences perhaps will help us re-imagine our organizations away from metrics of accountability, and formal and uniform managerialist practices.

Societal living – during the pandemic many of us have witnessed how the actions of some inevitably have had impact on others. These inherent interdependences cannot be overlooked. We’ve come to realize that nihilism and selfishness are not an option. The crisis has given us a chance to see that many of our everyday decisions reinforce certain inequalities, both social and economic. Finally, I hope that many of us have realized the importance of being active citizens, who not only make conscious choices, but also realize their potential as agents of change both individually and collectively.

When “Que Sera Sera…” is not enough: COVID-19 and the “elderly” population

The top 5 things I have learned about growing older during the COVID-19 global pandemic

By Sula Awad – August 2020

So, before I get to explaining my choice of title for this blog contribution, first let me prime your thoughts. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), by 2050, 22 percent of our global population will be over 60. Basically, by 2050 there will likely be A LOT of humans over the age of 60 gracing planet earth. As these humans approach their seventies, eighties, hopefully nineties and maybe even hundreds, they are likely to go through various personal, health and life-related journeys. These journeys may require them to adhere to or be influenced by various measures in place by institutions that negotiate public and individual behaviours. To me, the most interesting of these journeys are health related. In a perfect world, the 60+ age group would be served by comprehensive healthcare measures, policies and health services that can address varied lived journeys of healthcare crises and complexities – healthcare that facilitates the physical, psychological and social processes of ageing.

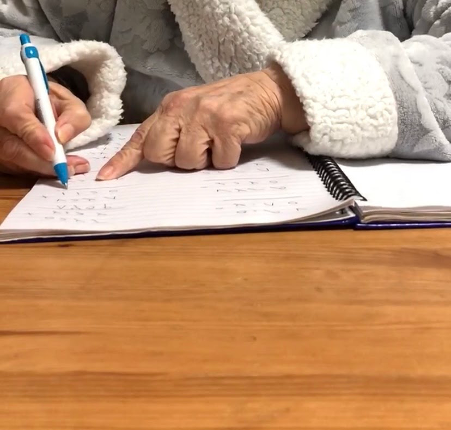

Not so long ago, my teammate invited the MISFIRES group to participate in a European study on the COVID-19 pandemic. The study wants to understand people’s experiences of the pandemic in relation to policies rolled out by different countries. The opportunity to participate in this study was wonderful. However, I did not anticipate how touched I would be by some of the enriching insights shared by some participants. Themes and insights that I did not anticipate emerged – most prominently, the lived experiences of the ageing population in the 60+ group. The most interesting insights were those that addressed the experienced marginality due to the COVID-19 policies for their age group. These insights led to interesting discussions around their lived experiences. They also married with my own experience of living with my grandmother (83) through the pandemic have taught me some things that I would like to share. Below I unravel the top 5 lessons I have learned.

1. Age“ism” is a very real thing

A stigma associated with being in the over 60, 70 or even 50 age group has been brought to light as a result of this global pandemic. Ageism is usually associated with malpractice in the workplace, however, it is a lot more widespread than we may perceive (The Economist, 2020).

According to Kenny and Taylor (2020), “ageism is the most prevalent type of ‘ism’ in society. Ageism impacts all aspects of our lives, including cultural and institutional aspects which determine policies and legislation. Examples of this are the definition of ‘premature death’ as occurring before aged 70, ‘dependency ratios’ which use 60 years of age as a cut off for dependency and a mandatory age of retirement. Ageism is particularly prevalent in health care systems. Respiratory illnesses, such as COVID-19, are constant reminders of ageism within the health care sector”. If we look at the above insights by Kenny and Taylor (2020) from the The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA), we can conclude that by turning a blind eye to the idea of ageism in the context of how we protect those growing older, we risk the negation of ageism being real for these people.

2. “Cocooning” can be a scary experience

“Cocooning” is a strategy outlined in Ireland and other countries to protect the (70+) age group from contracting COVID-19. This involved advising those in this age group to minimise human interactions for a prolonged period of time during this pandemic. Also, in Ireland there has been a strong effort on banning visitors at care facilities (Kenny and Traynor, 2020). This along with “cocooning” meant that residents of care homes had all visitors prohibited. This included all family members, siblings and partners.

Yes, your Instagram and Twitter pages may be garnished with heart-warming videos and photos of grandparents being visited and being delivered groceries. However, many of those cocooning genuinely do not have that luxury. This struck me when I really really thought about it. A plethora of us cannot and will not even spend 1 day without touching our phones, on average 2,617 times. How do we think the vulnerable in this group, especially those with underlying mental health challenges, are coping? Yes, a plethora of elderly can use and access smart technologies to stay in touch with their families virtually. However, many can lose their physical ability to pick up the phone and swipe “answer”. How many vulnerable people have been left without social interactions for weeks? How has this affected the mental health of the vulnerable in this group?

3. Pigeonholing individuals may be disempowering

“Cocooning” as outlined above, is a strategy to protect the older (70+) age group from contracting COVID-19, which categorises the above age 70 group homogeneously. This policy begs us to ask the question of; is thinking about this group (70+) as one holistic/ homogenous group an uncontentious idea? Can we paint all members of “the most vulnerable” or “older” age group with the same brush? Perhaps holistic health measures like these may create some forms of disempowerment to the communities they aim to protect.

Each person over the age of70 is created differently, with a different set of needs to establish optimal health outcomes. What if not all of this target group’s health needs are designed in the same way? What if some are able enough to carry on with their lives? What if some of those aged 70 and above do not want to cocoon themselves? What other options are available to them from a policy perspective? Does such a strict policy actually defy its initial purpose of protecting and shielding this group? What about those with progessive neurodegenerative diseases? Are such stringent broad policies effective when they fail to acknowledge the most vulnerable?

Our identities as individuals can often become fragile due to external forces. Our sense of self may be compromised or become a complex endeavour depending on our life stage. Thus, experiencing pigeonholing may be conducive to experiences of identity fragmentation for this group. Individuals progressing to older ages may already be facing identity related challenges. How does this labelling or targeting of these individuals through these policies affect their ability to transition into roles that may come with age?

It goes without saying that these measures are well intentioned, very appreciated and have been extremely effective in protecting the ageing population. However, the voice of these individuals is arguably missing in negotiating and formulating these measures. Perhaps going forward, there can be more input from those who need to be protected, to harvest an empowered ageing population that is heard.

4. Pandemics make access to essential health services challenging for this group, especially those with neurodegenerative disease

How many medications have been unintentionally missed during the pandemic? How many urgent appointments have been missed? What does it mean to be cocooning and receiving medical attention for patients in this age group with neurodegenerative disease like Parkinsons, Alzheimers, or other Dementias? During a pandemic, amid existing disorientation, this may mean that patients like this may walk into their living rooms filled with 3 nurses and a doctor they have never seen before all masked up. Imagine, you are already disoriented due to your illness and this is what you are acquainted with? To highlight my point, the ASI affirm that they are concerned about the “health impact on people living with dementia and family carers is not being adequately considered in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic” (Alzheimer’s Society of Ireland, 2020). Supplementarily, the AZI (2020), have asserted that many of those who previously attended daycare facilities for neurodegenerative disease have already switched to full time nursing home care due to the deterioration that was induced by the pandemic.

Further, I have also learned that certain neurodegenerative diseases have received little to no attention in Covid19 related public messaging and media (Alzheimer’s Society of Ireland, 2020). The voice of these patients matter and their age should not lead to limited support and representation.

5. The ageing have a voice. A voice that needs to be heard

The SHIFT Index study highlighted that we need to “Enable older people’s voices to be heard’ as currently the views and needs of this age group are not well represented in policy consultation (The Economist, 2020).

Thus, the ageing population should not be passive recipients of policies that are being designed without their voices, particularly when it comes to the area of health and illness. Perhaps understanding different models of involving these populations may be useful in implementing policies to reduce experiences of age related stigma, ageism or exclusion.

Multiple models exist to shape how health policy is designed with the involvement of the public. On one end of the spectrum there is the medical paternalistic perspective, where the patient is perceived to know little about health or medicine – how could they be expected to know or judge what is best for their health given their lack of clinical knowledge (Kennedy, 2003)? Secondly, we can look at it from the perspective of the doctor/policy maker having the expertise on how to fix the illness and then the patient having the expertise to know and imagine a life when the illness has been tended to. Here there is a mutual interactive relationship between both parties in achieving optimal health outcomes. However, perhaps we must recognise that this interactive model of patient care is maybe not as seamless as we would like to believe. This second example can conceive some groups/patients as not able or not given the opportunity to participate in their health needs. They are assumed to be too vulnerable or unable to express their needs. Some argue that even the mere suggestion of a participatory role in their health is “placing a burden of participation on them that they cannot bear” (Kennedy, 2003). However, by saying that only certain kinds of individuals have the capacity to be involved in the policies of their healthcare is potentially disempowering to those that belong to a certain category who are in good enough health to contribute their voice. Older age groups or vulnerable elderly groups “may need more time or more explanation, but they have their needs, their fears, their dreams, and their hopes like the rest of us. And like the rest of us, as citizens and as equals in their humanity, they have their claim to engage in their care” (Kennedy, 2003).

Okay, finally back to my confusing blog title (Que Sera Sera). This is a quote from my grandmother’s favorite Doris Day song (Que Sera Sera, Whatever Will be, Will be). She would always sing this line to me to comfort me when I was anxious about what the future would hold. Literally, this translates to “whatever will be, will be”. I would love to affirm this redemptive line when anxious about the policy measures, health services and noise around the ageing population at this time. However, I believe that Que Sera, Sera, is simply not enough. I hope to see a time when healthcare measures using this group’s voice are comprehensive, concise and inclusive. Over the coming months, I am hoping to start working on a research collaboration that attempts to understand the lived experiences of the ageing population in a pandemic context. Watch this space for further information and contributions from the MISFIRES team.

Stay safe and remind those in this targeted age group that they are seen and heard.

Sources

https://www.irishtimes.com/news/ireland/irish-news/covid-19-pandemic-revealed-ageist-attitudes-in-ireland-says-charity-1.4290725

https://ageingshift.economist.com/shifting-demographics-whitepaper/

https://alzheimer.ie/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/FINAL-Research-survey-results-on-need-1st-April-2020.pdf)https://alzheimer.ie/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/FINAL-Research-survey-results-on-need-1st-April-2020.pdf

https://alzheimer.ie/about-us/coronavirus-covid-19-update/

Kennedy, I., 2003. Patients are experts in their own field: The interests of patients and healthcare professionals are intertwined. Bmj, 326(7402), pp.1276-1277.

Surviving a pandemic 11,000 kilometres away from home

By Fernandos Ongolly – July 2020

Surviving a pandemic 11,000 kilometres away from home

What does it feel like to be a researcher locked down for months in a city 11,000 kilometres away from home? I never knew that is the kind of experience that I was going to go through when I moved to Ireland early this year. I packed my stuff in a town out of Nairobi and was dropped by my family at Jomo Kenyatta International Airport. I recall that rainy afternoon how I left in a hurry to catch my flight to Addis Ababa knowing that come May I will be able to fly home without any hassle. That day I did not see anything strange at the airport in Nairobi but when I got to Addis, I noticed thermal cameras all over as I searched for the next terminal where I was supposed to board my connecting flight to Dublin. I wish I knew what those cameras meant at that time, at least I would have prepared myself psychologically for what was coming to unfold in February for the whole world. I arrived in Dublin the next day in the morning where I was welcomed with a kind of weather I had only experienced in the movies. Fast forward, it has been four months, I have neither been able to fly back home or my family been able to visit me in Ireland. How did I keep sane in a foreign country?

I had amazing people around me

Working with colleagues that are supportive can make you feel at home even when you are miles away. They play a big role in ensuring that you know corners that ideally would have taken you months to know within a pandemic. There are many people that have never heard from their workmates since they last saw each other in February in the office, but the fact that my team meets regularly makes it easy to share what everyone is doing with their life in lockdown. For us we have never social distanced but just kept physical distances. My colleagues introduced me to their friends that we are friends now and has helped me to expand on my network of friends outside our corner office. Through such networks I have been able to engage in more than academia. I will also be lying if I do not recognize the efforts of my housemate in making life easy for me, through him, I became street smart!

I stepped out

The beauty of being new in a place is that the environment is also new to you hence there is a lot to see every day you step out! You will be amazed with how satisfying your neighbours’ flowerpots and kids playing around can be such entertainment for you. You will discover new physical features, species of birds, plants, and behaviours. I had never seen seagulls until I moved to Ireland! Looking at these amazing birds fly deep in land and taking long walks in the bushes of Blessington and Dublin kept my weekends going. There was always a new place for me to go every time I stepped out. At some point, my brain was so engaged with discovering new places that I forgot I was in this ‘alone.’ This also gave me the chance to reboot my brain after a long week of just being me with my computer.

I never planned to travel home

To avoid disappointments, I stopped planning for any travel back home or for any chances for my family to visit me in Ireland. Every time I thought of a plan, the government in Kenya or Ireland extended the travel restrictions and this could always end up with great disappointments. I learnt that the best time to plan is when you are on that flight back home or your family is on that flight to join you. However never celebrate until you are out of that airport gate; because you never know where you will spend your next 14 days. So, stop planning, relax, and enjoy the weather!

I became a Cook

I never knew how good a cook I was until this pandemic came. I discovered how draining it can be to sit behind your computer the whole day only for you to eat foreign food at the end of the day for dinner. At that point I had to figure out how to start making the kind of food I was used to eating back home. My wife sent me local recipe books and I could consult my mother too on how to cook some sophisticated meals like traditional mushrooms. After a month, I had become an expert and was cooking without referring to the recipes and I just fell in love with this new activity. Other than working and walking, I had something else productive to take at least two hours of my day. It was important to find a way of keeping off my computer.

I learnt to be a virtual dad

During this time, a lot of water passed under the bridge. My son turned one and I missed his birthday, he started speaking, and he is walking now. All this I missed! However, I had to do my online research on how to become a dad in this era of zoom, skype, facebook etc. I practiced all sorts of kid songs, recorded myself and shared with him. I made many virtual calls to keep in touch with him. The best moments for me is him being able to learn from me despite the distance. I had to innovate on how to keep in touch with the family. However, my 86-year-old granny does not understand why I have not been home for so long.

Am I longing to go back home?

Just like all of you reading this blog, we are all longing for that time that we will be able to see our family members again, we are longing for the time that the pubs will be open, we are longing for the day that we will meet our friends and colleagues, and that day that things will get back to normal. What will you do when the day comes? What if this is our normal? I have learnt never to anticipate anything and not to have any expectations for now. I will wait and enjoy what this beautiful country has to offer.

The Invisible Threads in Project Management

By Gemma Watts – June 2020

Connections

My life has changed considerably over the past few months with COVID19, and these changes have given me time to reflect on one aspect of project management that is not as visible as the operational day-to day tasks, but I realise now are as just as important. This key aspect to project management is the connections that you make in your role as a project manager. The relationships and networks that you engage with and become an integral part of, that adds to your sense of fulfilment in your daily working life.

Community

I work remotely from home now, as many of us are, and the “office” has become a slightly faded memory. The office is now no longer a place for people to congregate, to work together as a team and to share ideas and thoughts. The social aspect of work too has greatly diminished. The many planned and scheduled ZOOM calls do not give the same exposure or experience as those impromptu corridor chats. That opportunity to just stop and say hello has gone and in turn taking away that feeling of being part of a larger community. To some the “office” has become a place of fear with that dreaded commute to work, and having to share work space and workplace facilities again in the aftermath of COVID19. For others, the desire to return back to a life before lockdown and to a shared work place again is strong. Perhaps that community feel and the social aspect of the work place is a driving force in this.

Camaraderie

As a project manager, I know that it is important for the team to engage with key stakeholders, not just for disseminating the research findings, but to have conversations and share knowledge with, that will have a lasting impact and make a difference to society. At the end of the day, that is what we strive to achieve with research, it is about making a contribution and that, as a project manager, I wholeheartedly support.

But I am just realising how important networking or relationship building is to the actual project manager. Managing a project can be a lonely quest, as you are usually the only administrator on the project with a unique set of skills and attributes from that of the rest of the team. But through building relationships and friendships with other project managers, you get to feel connected to people who understand your role and what you do. Who have the same challenges and obstacles. These shared experiences and stories unite us in our journey to deliver a project to the best of our ability and help us to feel part of something bigger. These relationships provide a safe forum to discuss issues, to ask for help and to pool knowledge and insights. This peer to peer learning is an essential and invaluable resource that I am only now realising the importance of.

Project Officer (PO)

All European Commission (EC) projects use an online portal called the “Participant Portal” as a 2 way communication and document repository tool. But, in addition all projects are given an EC contact, a person that is responsible for assisting with any project related queries known as the “Project Officer” (PO). The PO can become a great source of help and provide much needed clarity when circumnavigating the EC requirements. Sometimes unforeseen circumstances can occur during the management of a project, such as COVID19 for instance, and by having that relationship with the PO in place, you have another source of support and guidance to assist you in your role as project manager. Building that relationship early on in the project makes it easier to contact the PO when you need to, rather than avoiding the PO because of other reasons, such as you don’t want to put the project on the PO’s radar, or because you are not sure how to go about it. Of all the POs I have dealt with, emailing them directly has been my preferred choice rather than using the formal communication channel of the participant portal.

Ethics Advisor

The ethical element has to be successfully navigated prior to data collection and this involves liaising with the internal ethics office in order to gain the much needed institutional ethical approval. However this is only the first step in the process, as the EC will have stipulated requirements that need to be met and approved by a dedicated EC Ethics Advisor. Again the relationship built with both the institutional office of ethics and the EC Ethics Advisor is so important in meeting these requirements and negotiating any deviations or deadlines.

Data Protection Officer (DPO)

In order to ensure compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), a working relationship had to be established with the UCD DPO. This involved demonstrating to the DPO that our project clearly addressed and conformed to GDPR, such as the 7 principles, Data Impact Protection Assessment (DIPA), and had a website privacy statement. Again, the relationship built with the DPO positively affected the progress and outcome of this engagement. These relationships do take time and commitment to develop, but they are essential in enabling the project to move forward and deliver against key project milestones.

Librarians

The UCD librarians have always been a great source of support and help in managing a project in areas such as the Data Management Plan (DMP) and the ‘FAIR’ (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable) principles. They have also provided assistance in meeting the EC’s desire for free online access to the project’s peer reviewed articles and/or research data by way of the UCD research repository. Linking to Open AIRE has been slightly problematic, and it has been a combined effort of both the librarians and I to overcome the hidden obstacles and be victorious in our endeavour. Our relationship has, and hopefully will continue to, stand the test of time.

Final word

Last and most importantly, in the hope of not sounding like an acceptance speech, I just want to thank all those invaluable connections, networks and relationships that I have been lucky enough to make in my journey as a project manager. The above is but just a few of these invisible threads that help tie together a project and I look forward to many more interactions.

African Solutions for African Problems: What I have learnt from COVID 19 Back Home

By Fernandos Ongolly – May 2020

So, I have been following news of COVID19 as they unfold in Africa. Being an African researcher living far away from home there were reasons for me to worry about my ‘country people.’ I made calls home every day to check on my family, but they seemed to be more worried about me than I was about them. Every evening if I did not make a call, they would call just to help me keep on track with the number of cases in Ireland, at a time when Ireland had around 1000 cases. There were no cases recorded in my country Kenya yet if am not wrong. This to me was because there were no efforts to test for COVID19 at that particular time in March – of course you cannot get what you have not gone out looking for. Business in Kenya and other African Countries continued as usual.

In my opinion one of the reasons my country people were not overly worried was that several folk theories were going round on who can contract COVID19 and how. Coming from trusted people in the community mostly through uncontrolled social media, these created a sense of security among not only Kenyans but most Africans who they thought that they were safe and COVID19 will never get close to their homes. Passenger flights from all over the world continued landing in most African nations as far as mid-March and some originated from hard hit areas with COVID19. Business went on as usual on the following grounds:

Africans cannot contract COVID19

This brought an assurance to Africans worldwide; at one time I was almost convinced by this theory too. When the first cases were being reported back home, they were all imported cases originating from Asia and Europe and none from within Africa. Africans on the continent never braced themselves early enough for a rough ride through lockdowns because they considered themselves ‘uninfectable’. In Kenya, the minister of health kept on assuring locals that they were safe since most of the cases that had been reported were imported. The government decided to fly back the National Carrier’s Boeing 787 from JFK from New York to Nairobi;’ I was tempted to go down to New York from Dublin to fly home in the highly popularised ‘Last Flight.’ All I know is that the pilot of that flight succumbed to COVID19 a few weeks after it touched down in Nairobi. We were never told how many people on that flight were infected. Mark you, the pilot was an African born and raised in Kenya. Can Africans contract COVID19 now?

Africa is too hot for COVID19

In one of the press conferences in the US, President D. Trump said that the virus is a flu that will pass when winter is over. Africans back at home celebrated because they never experience winter and considered themselves very safe from the virus. Other rumours went round that the virus cannot survive in temperatures above 20 degrees Celsius. Almost all African countries have an average temperature of above 20 degrees; this was another point of reassurance. Nothing major continued happening to contain the virus. However, cases were being reported in North Africa where temperatures go as high as 40 degrees Celsius.

Africa had Ebola and HIV experience

Some Africans looked at this as someone with the experience of complex writing skills being given vowels to read. Most people claimed that they had faced more than COVID19. To most Africans COVID19 was nothing close to Ebola and HIV. It was nothing to scare them based on the experience with these diseases, Africans felt reassured through fact that the continent survived deadly diseases before and that COVID19 was ‘just’ a flu that will come and go.

Africans are hardy and survivors

We Africans have passed through many hardships and we have survived. Before COVID19 there was a major invasion of locusts in Eastern part of Africa that caused a lot of damage to crops, somehow it came and passed. There have been drought and floods reported in some parts of the continent that were well survived. With the hardy mentality most knew that they are strong enough to withstand the infection when it comes and the only preparation that was put in place was ‘waiting for Corona to arrive.’

We were given faulty test kits

When some countries like Tanzania that had not put in place any serious preventive measures started testing for COVID19, they recorded far more cases in a day than what their neighbours had reported in a month. The conclusion was that the kits were faulty and unreliable. In Tanzania people were allowed to continue gathering in groups; going to church and other social activities that exposed them to the virus. By that time it was confirmed that Africans can also contract COVID19 but they were still complacent with executing preventive measures. Who bewitched us?

We have herbal remedies

This reminds me of an entourage that flooded a small village called Loliondo in Tanzania some time back when an old man announced to the world his concoction that cured all sorts of diseases. The condition was that you were to go and take it on location for it to work. The concoction was sold at an average price of 50 cents USD and people travelled from all corners of the world to queue for weeks to take their dose. Patients suffering from cancer, HIV among many other diseases were his number one clients. This is no different with COVID19 when Madagascar launched its COVID-Organic preventive drug with an ambitious goal to scale up all over Africa. Did we forget the Loliondo concoction? I’m not against COVID-Organic, if it works, I will be glad to have a bottle!

Light at the end of the tunnel

Despite the struggles and inefficiencies, there have been excellent measures put in place to contain the virus by most African countries. We are proud of Senegal as the first African country to come up with locally manufactured test kits that costed as little as one USD, hence opening an opportunity for mass testing. African nations have realized that it is possible to locally manufacture medical equipment and PPE materials and cut their dependency from their big brothers in the west and handouts from Asia. This has opened an opportunity for faster supply of medical equipment when needed at affordable prices. Other nations have constructed infrastructure such as wards and added their ICU capacities by over double to what they previously had, which will benefit more people post-COVID. This was done in record time. It may not be possible to effectively implement social distancing in Africa, but the spirit of Ubuntu has brought some sense of self-reliance among African nations that can be taken advantage of to strengthen their health systems long term. If there are positives from this current crisis, then I would think that COVID19 will leave health infrastructure footprints that will be useful in the future long after it has passed.

On libertarians and the UK pandemic doctrine

By Théo Bourgeron – April 2020

When the Covid19 virus was exclusively hitting China, much was written on how this pandemic event would be the “Chernobyl of Xi Jinping” and the Chinese Communist Party. Since it has been affecting almost exclusively Europe and Northern America, much is being written on the collapse of globalised neoliberalism and the success of the Chinese model. Over the past few days, I have been trying to substantiate some of these reflections by studying more deeply the UK doctrine to pandemic events. Detailed with great clarity by Prime minister Boris Johnson’s talk on 12 March and Chief Scientific Adviser Sir Patrick Vallance’s radio interviews, this doctrine consists in channelling the circulation of viruses, rather than repressing it, in order to build “herd immunity” in the UK population.

Although it is far from being exhaustive, my study shows that:

- This approach is far from being isolated. The Netherlands explicitly abide by the same approach, with Prime minister Mark Rutte talking about it in his 16 March speech. Except for Italy (ironically), which tried to aggressively prevent the spread of the virus from the onset of the crisis in China, in the first weeks of March there was an underlying ambiguity in the discourses of other European countries regarding whether they were following the UK or the Chinese approach.

- There are strong links between governmentality systems and the management of epidemic episodes. Michel Foucault has shown how the evolution from medieval governmentality to modern governmentality has involved a shift in the two main events that used to destabilise governments during centuries – epidemics and food shortages. The neoliberal order that rose in the 1980s also involved its own epidemic doctrine under the management of the WHO, with the support of the most powerful Western nations. Unfortunately, this organised neoliberal order is arguably coming to an end as several Western nations now openly promote the rise of a new world order based on post-neoliberal ideas – inspired from an authoritarian-flavoured libertarianism.

- Built between 2010 and 2017 by the UK Department of Health, the UK pandemic doctrine deeply reflects:

- The thought of the libertarian think-tanks of Tufton Street that already influenced the UK conservative party on many topics, ranging from Euroscepticism to climate change denying.

- The findings of behavioural economists that compose the Nudge Unit set up by David Cameron in 2014 in the Cabinet Office, including David Halpern, who participates to framing the response to the coronavirus crisis.

- This approach is not a deliberate choice by Prime minister Boris Johnson or the UK government. It also results from the state of the UK after several decades of reforms. It is described as a constrained choice by policymakers, given the configuration of the UK economy and the UK society – as such, it is a structural shift that reveals how epidemics will be treated in a post-neoliberal, libertarian-inspired world.

In my perspective, as the current late neoliberal accumulation regime is evolving, this pandemic event makes clear the tensions between people’s suffering (as people have to accept, in Boris Johnson’s words, “the early loss of loved ones”) and economic structures based on the maximisation of capital returns. In the same way as the current environmental, social and democratic crises, it is already resulting in social unrest situations that will require new modes of government.

More details on these reflections can be found in the April issue of Le Monde Diplomatique. Also available in English soon.

https://www.monde-diplomatique.fr/2020/04/BOURGERON/61622

Wait, did you just call me a plumber?

Some inner ramblings of an amateur Actor Network researcher.

By Sula Awad – October 2019

An introduction to me

Ok, I owe you an explanation about the plumbing. But now that I have your attention, let me first tell you a little bit about me. I am Sula. Foodie, wannabe exerciser, avid snacker, reader, and obsessed with navigating “health”. Why on earth have I decided to study “Healthcare Market Failures” for the next 4 years? Well, let’s take it back a notch. I have always been fascinated by the notion of “Health”. What defines health?, Is it a state or destination? Is it achievable or earned through our lifestyle choices? Is it just another loaded 5 letter word that we bash around, oh so flippantly? Is it even linked to diet or is that what “they” want us to believe? Can what we eat trump any medicines healing powers? Or even better; is food medicine? All of these inner ramblings have consumed my brain for as long as I can remember.

My interest in the study of health married with business began during my undergraduate degree in Business Studies and extended to my master’s in Strategy. The pursuit of both my degrees led me to conduct research projects such as “Assessing the Attitudes of Women Aged 18-25 towards their Sexual Health; shaping women’s health services to address psycho-social barriers”. And “A Critical Analysis of the Causes and Alleviators of Mental Health Related Presenteeism in the Workplace in existing empirical research”, and “A Stakeholder Analysis of Sustainable Health Enterprises”.

Clearly, my long lived flame with “health” encompasses many facets. Inherently, becoming a member in a project that was researching “healthcare markets” was a dream come true. Except there was one caveat; a significant theoretical knowledge gap presented itself to me. The empirical contexts of ‘MISFIRES’ work was really cool to me, however, I was anxious and clueless of the theoretical framings used here. However, the more I have read and mumbled juvenile questions to the team, the more familiar I have become with the range of theoretical stances that can be taken to explore this kind of research. This notion of “theoretical stances‘ nicely leads me on to the part of my blog I have been so very eager for you to get to – the “Wait, did you just call me a plumber” bit. The title of this blog is really the phrase that illuminates to me what my role as a researcher in this project will encompass.

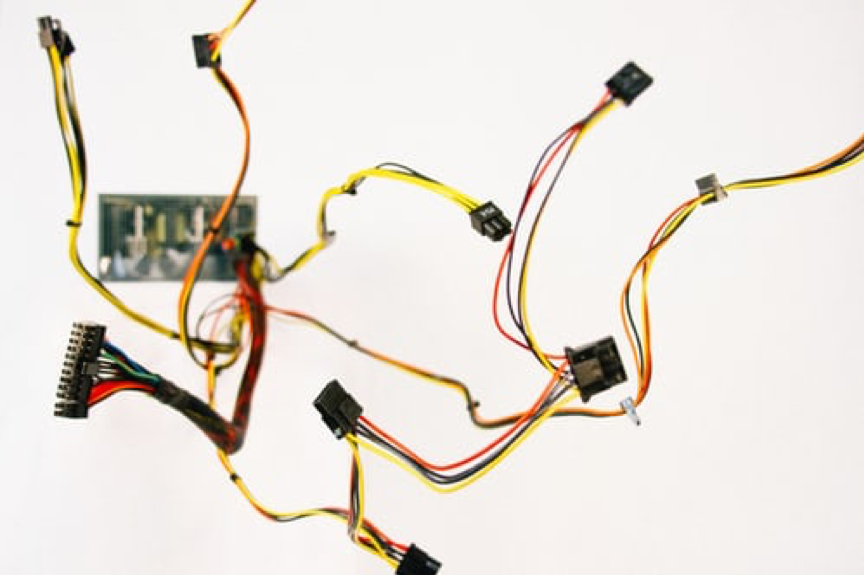

To really understand a market and its intricacies, navigating the “plumbing” first is a really crucial aspect. In one of our early reading groups, Susi, the project leader, mentioned that we are like “plumbers” when it comes to studying markets. I can reassure you that she did not mean the image of “plumbing” that you have embellished in your head right now. By definition, a plumber is “A person who fits and repairs pipes, fittings, and other apparatus of water supply, sanitation, or heating systems”. The key word in this definition is systems, and by systems, this means that the plumber attempts to examine/fix the components that make up these systems, rather than just their overarching functionality. The plumber does not just examine the macro level issues and forces that make up a water, waste or sanitation system, rather; she delves deeper and looks at individual components that meld with one another to make this system function as it does.

By focusing on the finer, more granular elements and how these interact with one another, she accrues a more tangible idea of what is happening. She can literally point her fingers at what is creating issues and breakdowns within that system. As a MISFIRES researcher, I aim to emulate this. However, instead of putting my plumbing kit on to examine pipes, fittings, apparatus/ fixtures, I use my conceptual and methodological plumbing tools to study “market actors”, in the hopes that they will shed light on the inner workings, interactions, issues and breakdowns of healthcare markets.

Another definition of a “Plumber” is “a person whose job is to connect and repair things such as water and drainage pipes, baths, and toilets.” The key word in this definition is “connect”. So, when I study different market actors and examine their interactions with their wider environments, my plumbing toolkit also demands that I draw logical connections between these interactions. The analogy I have provided above attempted to unearth what theoretical stance my research will take: an Actor Network Theory Approach.

Yet, plumbers and researchers, despite our similarities, also share differences. Plumbers fix systems, while researchers cannot. We can hope that our work can shed sufficient light on the inner workings of these healthcare systems so that the system may be better informed of how it works itself. This aspect of research can be frustrating at times; however, knowing that my work is contributing to knowledge and has the potential to be shared with others passionate in my area sparks so much excitement within me. Also, it may be important to note that, while a plumbers role may be unappealing or “unsexy” to some, it is fundamental. Perhaps this is another similarity between plumbers and researchers in this space.

So what am I actually researching?

Yes, the above reflections may seem highly conceptual, but these have been catalytic in shaping where I want my research to go. I am now researching how patients form and give life to markets when they feel as though mainstream medicine has failed to provide them with sufficient patient care. The empirical context I am hoping to explore this in is; diseases/illnesses that are often contested by orthodox medicine consensus.

So, I look at what and how actors are disturbing the markets mentioned above. I ask myself questions such as: are the market actors only humans? Is there material forces that are shaping how these patients are able or unable to disrupt these markets? How do the actors go about becoming fundamental parts of the system? What happens when different actors have conflicting narratives surrounding the existence of these markets in the first place? These are questions that I will continue to ask myself for the next while, but if you wish to know more about the answers to these questions, stay tuned for my next ‘MISFIRES’ blog series contribution. Analogies and inner ramblings will assuredly feature! 🙂

The Underestimated Horizons

of Philosophy

By Dr Ilaria Galasso – July 2019

A complicated question

One of the most complicated questions I can be asked – and unfortunately, like most people, I have been asked that question many times – is what I do. Or what my job is, what my field is, what my background is. The complexity of this question is not (only) related to the fact that the world of academic research is still quite esoteric, so that people who are not part of it often do not have clear ideas of what researchers do. In my specific case, it is complicated because, in any contexts, answering this question requires a series of specifications, of clarifications, and even of justifications.

The odd one out

I cannot just answer by mentioning the institute I am affiliated to. This would only generate confusion and misunderstandings. Currently I work at the UCD School of Business. Before that, I worked at the European Institute of Oncology. Before that, among others, I attended classes at the Department of Physics . And the most (apparently) odd thing is that, originally, I studied philosophy.

You can imagine the puzzlement of people I have not had contact with for a while, who remember me studying philosophy, when they find me in a molecular medicine institute. Or when they find me at a School of Business if they remember me at the European Institute of Oncology, or at the Department of Physics, or at the Department of Philosophy. Any of them. This is indeed something that requires some explanation. Am I desperately fickle? Well…maybe! But not in this case anyway. Then, am I a sort of “know-it-all”? I wish! But not at all. Quite the opposite: one of the main difficulties of my “tortuous path” is exactly that I have always been a sort of “do-not-know-anything” about the different subjects I was at different times immersed in, at least with respect to the people I was surrounded by. In all these contexts, I (and a few other people with me) have always been the different one, the odd one out.